June 6, 1944 – D-Day

On June 6, 1944, the invasion of German-occupied France by allied forces began. It was the beginning of the end of the war in Europe, which occurred 11 months later when the Germans surrendered on May 7, 1945. I was 13 years old. I followed the war intensely in those days, watching Pathe newsreels on Saturday mornings at the East End movie theater, reading every 15-cent issue of Life Magazine I could get my hands on, keeping a scrapbook of newspaper clippings. We each had our heroes as well as our casualties. Bobby Longtine, 6 years older than me, was our first neighborhood casualty. I will never forget when I saw the Gold Star hung in his parent’s window as I walked by the Longtine's home on the way to school. Bobby's younger brother, Jack, was a classmate of mine at East High.

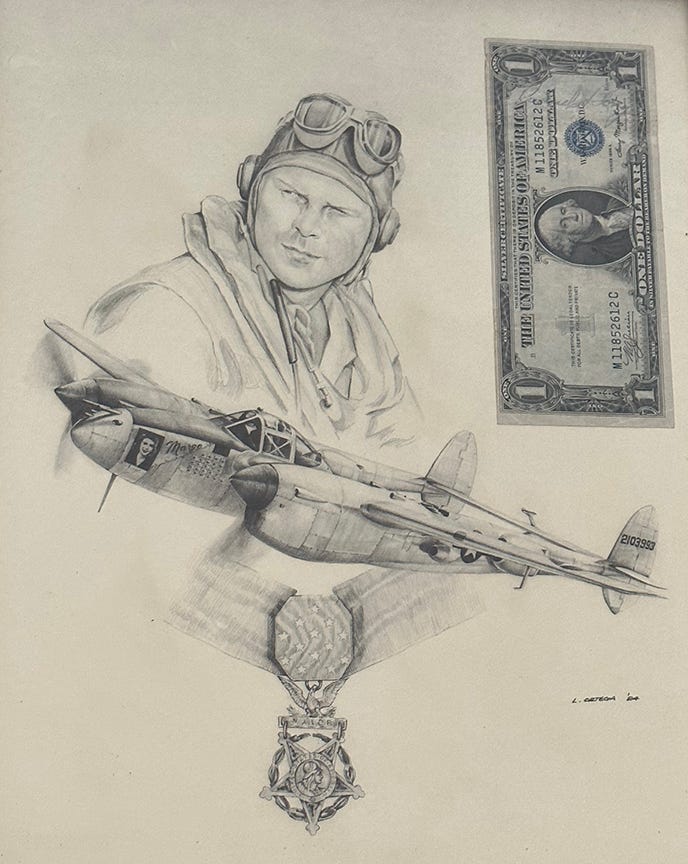

Dick Bong WWII Ace

Dick Bong, America’s leading ace, who flew 200 missions and shot down 40 Jap planes, was from Poplar, Wisconsin, about 15 miles from my home in Superior.

I remember our excitement when he married Marge Vattendahl, the sister of Bill, one of my good East High school classmates. How Major Bong thrilled us all when he brought his P-38, which he named “Marge,” to Superior, and flew it Chinese style – one wing low – down Tower Avenue, our main street, not more than a foot or two off the ground! He received the Medal of Honor from General MacArthur. MacArthur decided America needed a live hero, so Bong was sent “home for good” in January 1945. His assignment was to promote the sale of war bonds, in addition to his new role as a military test pilot. Unfortunately, he died on August 6, 1945, the day we bombed Hiroshima, test-flying one of the new fangled Lockheed jets. During the 1964 elections, I was active in Barry Goldwater’s presidential campaign. Goldwater had been one of Bong’s flight instructors.

To this day I cherish a drawing of Dick Bong, his P-38, Medal of Honor, and a dollar bill with his now-fading signature, an ancient birthday gift from my sister, Cathy.

Although Bong's War was fought against the Japanese in the Pacific, the airplane he flew, the P-38, had a remarkable role in Europe on D-Day. Its unique design made it a perfect plane to fly cover for the American, Canadian and British troops as they stormed the beaches of Normandy on D-Day. The P-38's twin motors and tails provided it with a distinguishable look, easily separating it from the Germans' Messerschmitt 109's, the backbone of the Luftwaffe's fighter force. Thus, the P-38s were less vulnerable to being shot down by friendly fire in the craze of the invasion.

D-Day - The War to End All Wars

The massiveness of our WWII buildup and effort was unbelievable. When the Germans occupied Paris in June 1940, the American army of 190,000 was smaller than the armies of either Sweden or Switzerland. Four years later, in May 1944, a month before D-Day, almost 8 million Americans were in uniform. The Eisenhower Foundation tells us that the D-day invasion, known as Operation Overlord, involved 156,115 soldiers, 12,843 aircraft, 6, 939 ships, and 195,701 naval staff.

Over the years, I've read a lot about the war. Joseph Balkoski's Omaha Beach: D-Day, June 6, 1944, really brought the sobering reality of D-Day home. On D-Day, starting at 6:30 a.m., landings took place at five beaches code-named Sword, Juno, Gold, Omaha and Utah. Faced with a hailstorm of artillery, machine gun, rocket, mortar and small arms fire, the 34,250 soldiers landing on Omaha Beach suffered the most D-Day casualties: 4,720.

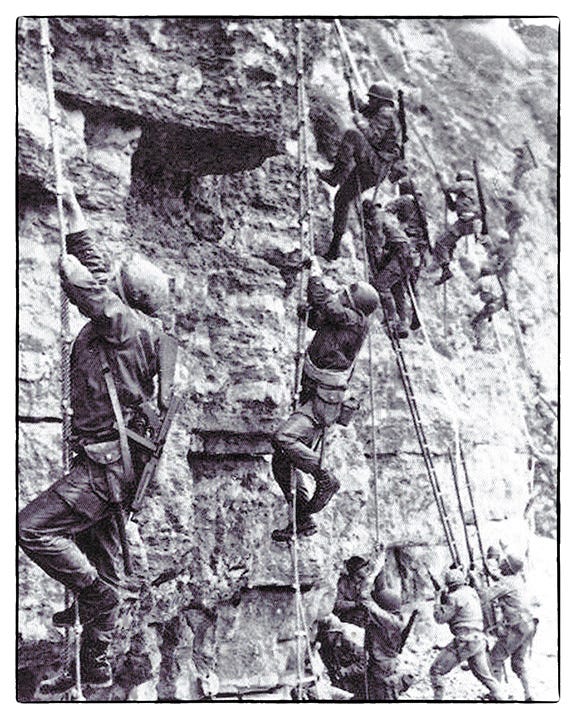

A look at the Rangers climbing Pointe du Hoc from Omaha Beach in face of German fire from the cliffs is a frightening reminder of the difficulty the troops had to overcome. President Regan paid a tribute to the Rangers on the 40th Anniversary of D-Day: "The Rangers looked up and saw enemy soldiers [on] the edge of the cliffs shooting down at them with machine guns and throwing grenades. And the American Rangers began to climb. They shot rope ladders over the face of the cliffs and began to pull themselves up. When one Ranger fell, another would take his place. When one rope was cut, a Ranger would grab another and begin his climb again.... Soon, one by one, the Rangers pulled themselves over the top...."

Balkoski reported an interview with Third Battalion Commander, Lt. Colonel Horner, who said, "The casualty rate normally is about one [killed] to seven [wounded]. [On D-Day] it was one to one." Balkoski concluded, "Such dreadful losses confirm that the eighteen-hour battle on Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944, was indeed one of the U.S. Army's most costly combats of World War II."

As I've pointed out in prior blogs, we Americans believed WWII was the war to end all wars. But the war wasn’t the war to end all wars. I was at the University of Wisconsin when the Korean War got in full swing in 1950, five short years after WWII. Several of my high school buddies who were drafted got trapped on the Chosin Reservoir when the Chinese intervened. They brought home tough stories. I was lucky, my 2 year stint in the Army started in 1954 as the war wound down.

Leakey-Ardrey Lecture

In 1971, during the Vietnam War, anthropologists Louis Leakey and Robert Ardrey lectured at the Leakey Foundation about “Aggression and Violence in Man.” During their discussions Ardrey said, “After our experience in Vietnam I would hope Americans would learn that [a war] of intrusion is not a rewarding way of life.” There were some pretty active Vietnam protests back then, and there was singers Peter, Paul and Mary and their soulful Where Have All the Flowers Gone.

But we didn't learn from Vietnam any more than we learned from WWII or Korea, or from any of the other undeclared wars. The 130 plus undeclared wars Americans have been in since WWII took a hefty portion of our national budgets and represent a large part of our growing national debt. These wars also killed too many of our young men and women and saddled too many battle survivors with PTSD. The wars also cause a lot of “collateral damage” - civilian death and destruction in the countries where we intrude. But, today’s wars of intrusion draw few protestors, probably because today's soldiers are not conscripts and because we are not asked to sacrifice back home as we were in WWII.

If we travel around our globe in this our 23rd year of the 21st Century, from Central and South America through the Middle East to Myanmar and China (with side glances not just at Russia, but at the attempted insurrection following our 2020 election), any close look at human conduct can be pretty discouraging. Why can’t we stop our penchant to solve our problems with violence?

Was Raymond Dart (who discovered Australopithecus africanus in 1924) right in the 1950s when he developed the theory that interpersonal aggression was the driving force behind human evolution, explained in his The Predatory Transition from Ape to Man? Is there No End to War as Walter Laqueur wrote in 2003? Has man always fought, as Steven LeBlanc concludes in his Constant Battles? Was Konrad Lorenz right about man’s instincts of aggression against his fellow man in his On Aggression? Was Geoffrey Perret right in his Country Made by War that war is what made America great?

Or was Rousseau‘s romantic view right – do we come from the stock of “Noble Savages,” peaceful species who lived a life worthy of our reconsideration? Or, is Rousseau’s idea akin to Plato’s “Noble Lie”?

As I pondered these thoughts, I returned to the 1971 Aggression and Violence in Man Leakey Foundation lecture of Robert Ardrey (author of several books on early man and evolution, including African Genisis) and Louis Leakey (who discovered the origins of man in the Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, Africa).

Ardrey was of the view our killer instinct evolved over one or two million years, from our early experiences as a hunter, and was a necessary trait for survival. Louis Leakey (somewhat supported in the 1981 book of his son, Richard) disagreed and attributed our penchant for aggression to man‘s societal development, beginning as communities of cave dwellers, where prehistoric man gained his control over fire, and speech and socialization evolved, products of the last 40,000 years or so.

Leakey said, “(W)ith the arrival of real speech, although it has done a great many beautiful things, at the same time it has done certain awfully bad things, because it gave us time and leisure to invent ideas and some of those ideas, I am afraid, were the causes of our aggression.“ Ironically, two years after the debate, Leakey's protégé, Jane Goodall, confirmed Audrey’s conclusions after she witnessed chimpanzee tribal raids in Gombe. Until she witnessed the raids, the widely held belief was that chimpanzees, our nearest evolutionary relatives, were peaceful - and just maybe Rousseau's noble savage theory of our evolution was right. The deadly raid of a chimpanzee tribe into the territory of another tribe changed all that. Goodall concluded, “The chimpanzee has clearly reached a stage where he stands at the very threshold of human achievement in destruction, cruelty and planned conflict.”

Among Robert Ardrey’s and Louis Leakey’s conclusions is that man has been aggressively “territorial.” Individual man and societies of men value territory, seek territory, and defend territory. Territory is a prime source of human conflict. Ludwig von Mises, in Socialism, his 1932 defense of capitalism, wrote “All ownership derives from occupation and violence. ... It is no accident that it is precisely in the defense of property that Law reveals most clearly its character of peacemaker.”

The importance of “territory” and evidence that Chimps, like man, fight and kill for territory, was the subject of a June 2010 article in Current Biology, “Lethal intergroup aggression leads to territorial expansion in wild chimpanzees.” Although there are advocates today against territoriality, such as Andreas Faludi in his 2018 The Poverty of Territorialism, any reflection on the global politics of the 21st Century confirms that we haven't evolved very far from the chimpanzees when it comes to territory.

As Ardrey and Leaky neared the end of their talk, Ardrey observed, “Evolution makes difficult to learn that which is not survival value. ... It is easy to learn to kill to hunt. And now we have to unlearn to kill and it is difficult.” Leakey agreed, adding, “(E)ither we will be destroyed ... or we are going to save the world for our future generations - for our children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren. One way or the other. And I think we have to do it now. That is the lesson from our study of the past.”

Leakey advised in the “Q & A“ following the lectures that to live peacefully and overcome our propensity for aggression, people of all backgrounds must intermingle, mix, and become truly global until mankind realizes “they are all one and the same. … You can’t really kill people if you have a real feeling that they also have a faith and are meaningful. … Because of the destructive influences of dogmas and doctrines as distinct from faith, we are letting young people lose faith when they don’t have to lose. And having lost faith … they are not willing to abandon violence. If you believe that the person is something worthwhile, you don’t stuff him out.”

Jared Diamond concludes similarly in his The Third Chimpanzee, “When I try to think of reasons why nuclear weapons won’t inexorably combine with our genocidal tendencies to break the records we’ve already set for genocide in the first half of the twentieth century, our accelerating homogenization is one of the chief grounds for hope.”

How Do We Honor D-Day?

So how do we Honor D-Day, our “Longest Day?” We squelch our aggressive instincts, we work at becoming global in our understanding others, and above all we become reverent for life and for peace.

For me, 1954 Nobel prize winner Albert Schweitzer said it best:

A man is ethical only when life, as such, is sacred to him, that of plants and animals as that of his fellow men, and when he devotes himself helpfully to all life that is in need of help. As soon as man does not take his existence for granted, but beholds it as something unfathomably mysterious, thought begins.

By having a reverence for life, we enter into a spiritual relation with the world. By practicing reverence for life we become good, deep, and alive. By respect for life we become religious in a way that is elementary, profound and alive. I can do no other than be reverent before everything that is called life. I can do no other than to have compassion for all that is called life. That is the beginning and the foundation of all ethics. The man who has become a thinking being feels a compulsion to give every will-to-live the same reverence for life that he gives to his own. He experiences that other life in his own.

An impressive memorial remembrance of the spiritual value of American values at risk. Something that every generation can capture for itself. Thanks Dick Jacobs.

Very deep in thought and meaning. Man’s inhumanity to his fellow man is our destruction .